The Perils of America’s Unusual Mortgage System: 30 Years of Entrapment

November 19, 2023 | by Kaju

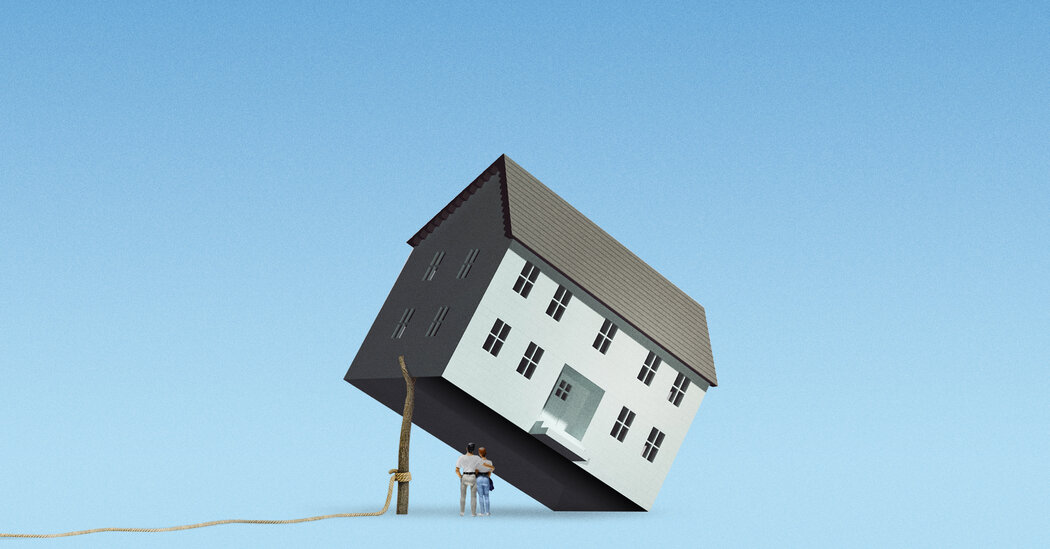

Getting a home was difficult even before the pandemic. Now, it’s even more challenging.

Costs have risen by nearly 40 percent over the last three years, exacerbating an already exorbitant price tag. The availability of homes has also decreased by nearly 20 percent during the same period. Additionally, interest rates have spiked to a 20-year high, diminishing purchasing power but not significantly affecting prices, contrary to typical economic patterns.

For existing homeowners, none of these developments pose a problem. They have been shielded from escalating interest rates and, to a certain extent, from rising consumer prices. Their homes have surged in value, and their monthly housing expenses remain relatively stable.

A major reason behind this disparity is a distinct and common feature of the U.S. housing market: the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage.

This mortgage is so prevalent that its peculiarity is easily overlooked. Due to its fixed interest rate, homeowners can freeze their monthly loan payments for up to three decades, even if inflation escalates or interest rates increase. Moreover, since most U.S. mortgages can be paid off early without penalty, homeowners can simply refinance if rates drop. This allows buyers to reap the benefits of a fixed rate without taking on the associated risks.

John Y. Campbell, a Harvard economist, has labeled it a “one-sided bet,” contending that the 30-year mortgage contributes to inequality. He points out that if inflation surges, lenders lose while borrowers win. Conversely, if inflation drops, borrowers can simply refinance.

This setup is unique to the United States. In other countries like Britain and Canada, interest rates are usually fixed for only a few years, spreading the impact of higher rates more evenly between buyers and existing homeowners. In Germany, fixed-rate mortgages are common, but borrowers cannot easily refinance, subjecting both new and longtime owners to higher borrowing costs. Denmark has a system similar to that of the United States, albeit with larger down payments and stricter lending standards.

The United States stands out with its extreme system of winners and losers, where new buyers face borrowing costs of 7.5 percent or more, while two-thirds of existing mortgage holders pay less than 4 percent, resulting in a $1,000 difference in monthly housing costs for a $400,000 home.

Selma Hepp, chief economist at CoreLogic, characterizes it as a market of “haves and have-nots.”

Not only do new buyers deal with higher interest rates than existing owners, but the U.S. mortgage system also discourages existing owners from selling their homes. This is because if they move, they would have to forfeit their low interest rates and opt for a considerably more expensive mortgage. Consequently, many are choosing to remain in their current homes, foregoing the additional bedroom or enduring a longer commute for a bit longer.

The result is a stagnant housing market, with few affordable homes for sale. Consequently, sales of existing homes have plummeted by over 15 percent in the past year, reaching their lowest level in over a decade. Many millennials are finding it increasingly challenging to break into the housing market, leading to a prolonged wait to purchase their first homes.

“Affordability, regardless of how it’s defined, is at its lowest point since mortgage rates were in the teens back in the 1980s,” remarked Richard K. Green, director of the Lusk Center for Real Estate at the University of Southern California. “We implicitly favor incumbents over newcomers, and there’s no compelling reason for that preference.”

A ‘Historical Accident’

The origins of the 30-year mortgage date back to the Great Depression. During that period, many mortgages had terms of 10 years or less and were not “self-amortizing”. This meant that borrowers had to repay the full principal at the end of the term, compelling them to take out a new mortgage to settle the existing one.

However, when the financial system faltered and home values plummeted, borrowers were unable to rollover their loans. At one point in the early 1930s, almost 10 percent of U.S. homes were in foreclosure.

In response, the federal government established the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, which utilized government-backed bonds to purchase defaulted mortgages and reissue them as fixed-rate, long-term loans. The government then sold these mortgages to private investors, with the newly formed Federal Housing Administration providing mortgage insurance to assure investors that the loans would be repaid.

Over time, the mortgage system evolved, with the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation giving way to Fannie Mae and subsequently Freddie Mac. The G.I. Bill led to a significant expansion and liberalization of the mortgage insurance system. The savings-and-loan crisis of the 1980s contributed to the ascendancy of mortgage-backed securities as the primary funding source for home loans.

By the 1960s, the 30-year mortgage had become the dominant means of purchasing a house in the United States and has remained so ever since, with fixed-interest rate mortgages accounting for nearly 95 percent of existing U.S. mortgages. The 30-year term particularly prevails, with over three-quarters of these mortgages set at that duration.

The 30-year mortgage’s ubiquity is, in part, a historical accident according to Andra Ghent, an economist at the University of Utah. Nonetheless, the government played a crucial role in this development, as most middle-class Americans couldn’t secure a bank loan at a fixed rate without some form of government guarantee.

Edward J. Pinto, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, and other critics from across the political spectrum argue that although the 30-year mortgage may have been advantageous for individual home buyers, it has not been as favorable for overall homeownership in the United States. The government-subsidized mortgage system has bolstered demand without commensurate focus on enhancing supply, resulting in an affordability crisis predating the recent surge in interest rates and a homeownership rate that is unimpressive by global standards.

Skylar Olsen, chief economist for the real estate site Zillow, asserts that over time, the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage likely erodes affordability.

Research indicates that the U.S. mortgage system has also exacerbated racial and economic inequality. Wealthier borrowers are more likely to refinance, resulting in financial disparities over time, even if borrowers start with the same interest rate.

Vanessa Perry, a professor at George Washington University, who studies consumer behavior in housing markets, states that “Black and Hispanic borrowers, in particular, are less likely to refinance their loans.” She adds that there’s a long-term equity loss as “they’re overpaying.”

‘Who Feels the Pain?’

Hillary Valdetero and Dan Frese represent opposite ends of the mortgage spectrum.

Ms. Valdetero, 37, purchased her home in Boise, Idaho, in April 2022, locking in a 4.25 percent interest rate on her mortgage just before rates rose to nearly 6 percent by June.

On the other hand, Mr. Frese, 28, relocated to Chicago in July 2022, amidst increasing rates. Presently, he lives with his parents, saving up with the hope of buying his first home, as rising rates push that dream further out of reach.

The differing circumstances of Ms. Valdetero and Mr. Frese have broader implications beyond the housing market. Interest rates are the Federal Reserve’s primary tool for controlling inflation. However, fixed-rate mortgages diminish the impact of these policies, necessitating a more aggressive approach by the Fed.

Mr. Campbell contends that there are ways to reform the system, including encouraging more buyers to opt for adjustable-rate mortgages. While higher interest rates have led to a slight increase in the share of buyers selecting the adjustable option, it remains a slow shift—from 2.5 percent in late 2021 to about 10 percent currently.

Other critics propose more extensive changes. Mr. Pinto advocates for a new type of mortgage with shorter durations, variable interest rates, and minimal down payments, which he argues would enhance affordability and financial stability.

However, practically, few anticipate the disappearance of the 30-year mortgage. With Americans holding $12.5 trillion in mortgage debt, mostly in fixed-rate loans, the existing system has powerful stakeholders certain to resist any changes that could jeopardize the value of their primary asset.

Instead, the stagnant housing market is likely to gradually thaw over time. Homeowners may decide to sell despite the prospect of a lower price. Likewise, buyers will adapt. Many experts predict that even a slight decrease in rates could spur a substantial surge in activity, making a 6 percent mortgage seem more palatable.

Nevertheless, this transition could take years. Ms. Valdetero expresses her gratitude for entering the market at the right time, realizing the plight of those who missed the opportunity.

RELATED POSTS

View all